Orthographic Mapping: What You Need to Know

There’s been a lot of buzz in the literacy world about the importance of orthographic mapping. We hear this term often, but what does it actually mean?

We’re going to dive into the stages of reading development, as well as discuss what orthographic mapping is, what it isn’t, and how we can help our students build strong orthographic maps.

Stages of Reading Development

We already know that reading is a complex process that includes multiple stages of reading development. Before they ever begin reading, children acquire language, learn how books work, and begin recognizing that symbols have meaning (such as the “golden arches” that mean McDonalds).

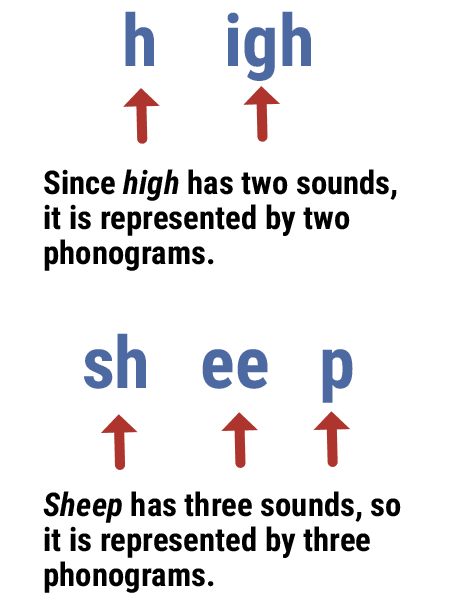

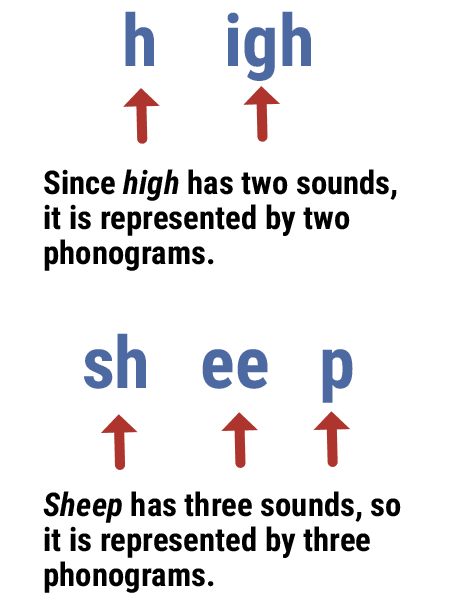

As they move into the next stage, children begin learning the alphabet and letter-sound correspondences. For example, they learn that the letter d makes the /d/ sound. The more often the child practices seeing, hearing, saying, and eventually writing the letter-sound correspondence, the stronger the connection that forms between the letter and its sound.

As readers move from learning the alphabet to decoding, they start out by painstakingly sounding out each individual letter in a word and then blending those sounds back together to form a whole word. This process is necessarily slow at the start, but the more and more practice a child gets, the quicker they become at recognizing the sounds of each letter and blending them together.

It is during this stage that orthographic mapping begins. As readers form increasingly stronger letter-sound correspondences and are able to sound out words more quickly, the letters and sounds of those familiar words are bundled together and stored in long-term memory for quick retrieval later.

With practice, children begin “reading ‘like they talk’ and have strategies to help them decode words and read with understanding.”1 They might still need to sound out unfamiliar words, but for the most part, they’re able to read with increasing fluency.

As fluency develops, students begin to achieve what we call automaticity, in which the child reads many words without even thinking about it. That’s because the words are now stored in long-term memory, and the brain can recall them immediately upon seeing them. In other words, the words have been orthographically mapped.

As children achieve reading fluency, they go from learning to read to reading to learn. They now have the word attack skills to decode unfamiliar words, and they “often read material that has many viewpoints and more complex language and ideas. They draw on what they know from other reading material and experiences to judge what they read and come to conclusions.”2 This stage of reading is only possible because of orthographic mapping.

So what is Orthographic Mapping?

David Kilpatrick describes orthographic mapping as

“the mental process we use to permanently store words for immediate, effortless retrieval. It is the process we use to take an unfamiliar printed word and turn it into an immediately recognisable word”.3

This process of orthographic mapping happens faster for some children and slower for others, but for a child who is being taught to read using a systematic phonics approach, each word that a child can read automatically has been orthographically mapped. We can’t see the process happen, but we know it has happened because the child reads the word automatically without having to think about it. The brain connects the letters and sounds in a word together, bundles them up along with the word’s meaning, and stores it away to be automatically retrieved when encountered in a text. The child will no longer need to sound that word out because it has become a sight word for them.

The process overlaps quite a bit. A child may have the word cat already orthographically mapped while still working on sounding out more complex words such as foxes or enough. The process of orthographic mapping is also ongoing, and as long as a person continues to read widely throughout their lifetime, it never really stops.

As you’ve been reading this article, you’ve probably done so mostly on autopilot because you’re a fluent reader. You’ve seen the words in this article so many times that you don’t even have to think about how to pronounce them or what they mean. It’s possible that the word orthographic was new and needed some thought, but even if that were the case, by the end of this article, you would have read it enough times to have it mapped in your own mind. That’s because our brains are so efficient that most of us only need 1 to 4 exposures to a written word for it to become instantly familiar and, therefore, orthographically mapped!4

What Orthographic Mapping Is Not

As we talk about orthographic mapping, though, it’s important to discuss what it is not.

One common misconception about orthographic mapping is that it’s the same as memorizing sight words. That’s simply not true. Even though a successfully mapped word is read immediately on sight and, therefore, becomes a sight word, not all sight words have been orthographically mapped.

The sight word approach is usually a whole-word, rote memorization approach in which children are taught a list of words by repeatedly showing them each word (on a flashcard or list) and having them say the word. After enough repetitions, children will eventually be able to recognize the word on sight.

However, because the children don’t go through the process of sounding the words out, there’s no connection between the graphemes and phonemes in those sight words. Therefore, those words are never “mapped” in their minds – no connection was made to the words’ sounds, meanings, or spellings.5

Another misconception is that orthographic mapping is a teaching method. This is also not true. Instead, orthographic mapping is “a mental process used to store and remember words. It is not a skill, teaching technique, or activity you can do with students.”6

We can certainly teach skills that enable students to develop stronger orthographic maps, but the process of orthographic mapping itself is done in the child’s mind as they make their own connections.

Helping Our Children Build Strong Orthographic Maps

So then, if it’s not a teaching method, how can we help our children build these strong orthographic maps?

First, we need to help our children develop solid phonological and phonemic awareness skills. Teaching concepts such as rhyming, counting syllables, blending, and phoneme manipulation help children develop these crucial skills.

Second, we can help children learn to segment words into their phonemes. This may look like using a token for each sound in a word or using tools such as Elkonin boxes to help students identify the individual sounds in each word during spelling.

Finally, we can teach reading and spelling using explicit, systematic phonics programs, such as All About Reading and All About Spelling. By helping our children make strong grapheme-phoneme connections, teaching them essential skills such as blending and segmenting, and giving them ample exposure to fully decodable words, we set them up for the greatest chance of developing strong orthographic maps.

Final Thoughts and Resources

While this topic is complex, the process of teaching a child to become a proficient reader and speller doesn’t have to be! Our programs are designed to teach these important phonological and phonemic awareness skills, and they include multi-sensory activities that promote orthographic mapping.

For more information and ideas, please check out these wonderful resources:

_________________________

1 Learning About Your Child’s Reading Development. National Center on Improving Literacy. https://improvingliteracy.org/brief/learning-about-your-childs-reading-development/index.html

2 Ibid

3 fivefromfive.com.au. How we develop orthographic mapping. https://fivefromfive.com.au/phonics-teaching/essential-principles-of-systematic-and-explicit-phonics-instruction/how-we-develop-orthographic-mapping/

4 Ibid

5 Farmer, Jessica. Orthographic Mapping: Training the Brain to Read. Literacy Edventures. https://www.literacyedventures.com/blog/orthographic-mapping-training-the-brain-to-read

6 Sedita, Joan. The Role of Orthographic Mapping in Learning to Read. Keys to Literacy. https://keystoliteracy.com/blog/the-role-of-orthographic-mapping-in-learning-to-read/

Kim

says:I’m use the tools I have learned from your blog for my tutoring business! Thank you for all the insight.

Paula D

says:My son has gone through All About Spelling levels 1-8. I have really appreciated this curriculum. I am considering using All About Reading based on my experience with AAS.

Christy

says:All about spelling has helped my 11 year old learn to spell. I almost lost hope. I now have a 5 year old that will need to learn to read. I have chosen to go with all about reading based on my experience with all about spelling working so well.

Allyson Wren

says:This is one of the reasons I love AAR it has been so helpful especially with my son whose severely dyslexic.

Joanie Burns

says:This is so spot-on! The more I dig into the “science of reading,” the more thankful I am that I was able to choose All About Reading for my first grade classroom! It has a grwat foundation.

Kelly

says:This is great information as I’m currently teaching this to my special needs child! Great resource, thanks

Revati

says:I assist to a special child.

Dee Tempest

says:I assist with homeschooling for my grandson who is nearly 8. Although we can see small steps happening he has never had interest in reading. Enjoys been read to, looking at books and loves games. Moving forward but slowly! This program has offered so much by just reading the blogs. Thank you all. This article was great and need the three P’s -patience, positivity and practice.

Patty

says:One of the aspects of All About Learning Press that I love the most is that they include so many free resources about reading and spelling on their site, such as this article about Orthographic Mapping! These resources are filled with research-based information about how to teach reading and spelling, and they also include fun activities that teachers, tutors, and parents can use with students to help them enjoy learning to read, which will encourage a life-time love of reading for these students. Thank you so much for all of the wonderful free resources that you continue to provide for teachers and parents! They are truly informative and helpful!

Amy

says:This was a helpful read.

Amy

says:This is helpful.

Maria G

says:Great info. I’ve been finding the AAR methods so helpful for my struggling reader!

Jennifer Penberthy

says:This is helpful! Thank you!

Sara

says:So encouraging!

Katherine

says:Thank you for this!

Alison

says:Thank you for this great breakdown.

Danielle

says:This information is so helpful. I think it did a really great job of breaking down a complex topic to make it understandable.

Kelli Griffith

says:My son has speech apraxia. I think this is one of the reasons that reading is so difficult for him. I’m definitely going to research more on this. Great article!

Robin

says: Customer ServiceKelli,

We have had great reports about our materials and students with apraxia of speech. Here is an example of the feedback we have received about this:

If you are on our Facebook Support group, you can also check out these conversations:

Is AAR effective for children with speech issues?

Does anyone use AAR with a child with speech delay or Apraxia?

If you aren’t a member of our Facebook support group, you’ll need to request to join to be able to access these conversations.

If you have specific questions or concerns, let me know here or by email at support@allaboutlearningpress.com I’m happy to help!

Jacquie

says:This is interesting. I have not heard of this, and am intrigued by the content. I look forward to doing more research on the topic.

Robin

says: Customer ServiceJacquie,

I’m glad we could help you learn something new! Have fun researching!

Andrea

says:This article is so very helpful! Thank you!!

Robin

says: Customer ServiceYou’re welcome, Andrea! So glad this was helpful!

Tina

says:This is so helpful!! Thank you!! I’m going to be saving every blog post 🤣

Robin

says: Customer ServiceYou’re so welcome, Tina! I’m glad this is helpful.

Amber Booth

says:So much great information. My daughter loves reading now using AAR.

Robin

says: Customer ServiceThank you, Amber. It’s wonderful to hear that All About Reading is helping your daughter enjoy reading!

Crystal

says:This is helpful information to know, thanks for sharing!

Robin

says: Customer ServiceI’m glad this is helpful for you, Crystal. You’re welcome.

Adrienne

says:So informative!

Robin

says: Customer ServiceThank you, Adrienne!

Cindy

says:This is very interesting. Thank you for the article!

Robin

says: Customer ServiceYou’re welcome, Cindy!

Romelia

says:Nothing like the craziness of reading English to show how incredible our brains are! :) thanks for the great program and info to help make it an easier to teach!

Robin

says: Customer ServiceRomelia,

Oh, yes! Our brains are fascinatingly effective at very, very complex tasks!

Nora

says:Thank you for this helpful article!

Robin

says: Customer ServiceYou’re so welcome, Nora!

Anna K.

says:This is such an amazing article! What an amazing way God designed the human brain!

Robin

says: Customer ServiceThank you, Anna! Yes, the brain is such an amazing design!

Emilie Barnes

says:So important to include the “what it’s not”! Very helpful!

Robin

says: Customer ServiceThank you, Emilie! Glad this was helpful!

Jessica

says:Thank you for this! It’s so helpful to understand how the mind works to be successful!

Merry

says: Customer ServiceYou’re welcome! Yes, it really helps you understand what you are working toward when you are “in the trenches” with teaching!

Heidi

says:I love reading about Orthographic mapping. I was going to incorporate some Elkonin boxes and was happy to see you wrote an article about it :)

Merry

says: Customer ServiceIt really is so fascinating to understand all the things going on in the brain as kids learn to read. Great idea to start incorporating Elkonin boxes! (If you have the Letter Tiles app, tap on the screen anywhere to create a gray Elkonin box!)