A Parent’s Guide to the Neuroscience of Dyslexia – Part 2

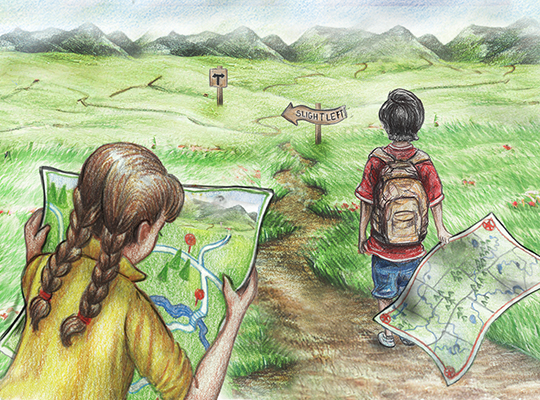

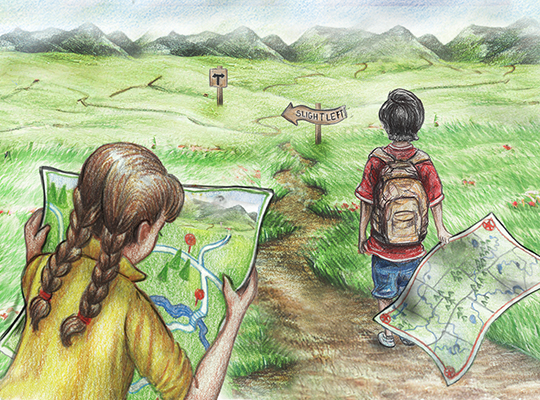

In Part 1 of A Parent’s Guide to the Neuroscience of Dyslexia, we discussed the parts of the brain responsible for language development and reading processes, how neurotypical children learn to read, and the neurological impact of dyslexia on language and reading skills. We discussed the fact that for most dyslexic learners, it’s as if their brains take the longer, more scenic mountain roads instead of the faster, more direct interstates when reading and spelling.

It can be a painstaking and frustrating process for a dyslexic student to learn to read.

However, the great news is that we don’t have to leave our students stuck on those backroads, forever struggling to make sense of the reading code. Relying on current neuroscientific research, specialists have repeatedly proven that with the right approach, it is possible for dyslexic students to form and strengthen the neural connections needed to read fluently and spell accurately. In short, it’s possible to “rewire” the dyslexic brain.

The question is: how do we do that?

What It Means to “Rewire” the Dyslexic Brain

Before we jump into the “how,” it’s important to clarify that in “rewiring” the dyslexic brain, we aren’t “curing” dyslexia. There is no cure, but we can strengthen the connections the brain has made and in doing so, make the process of reading more efficient. And because the brain always wants to conserve resources and energy, if we go back to the mountain road versus interstate analogy, it’s quite possible (and very likely) that as we work to improve those roadways, the brain will develop new and faster routes – or shortcuts – that improve reading fluency and spelling automaticity.

So even though there is no “cure” for dyslexia, providing the proper tools and interventions to strengthen those neural connections does teach our children how to overcome dyslexia.

So now let’s dig into the how.

The Right Approach to Teaching a Dyslexic Student to Read and Spell

In the 1930s, Samuel T. Orton and Anna Gillingham developed the Orton–Gillingham Approach to teaching reading and spelling to students with “word-blindness,” now called dyslexia.1 Their groundbreaking research and methodology paved the way for teaching dyslexic students how to read and served as a foundation for later scientists and educators to build upon. In recent years, with the use of specialized brain imaging, as well as rigorous scientific testing, we now have evidence-based practices for successfully teaching reading and spelling to dyslexic students.

The National Reading Panel was one such group that conducted rigorous scientific research, and their research “concluded that there [are] five essential components to reading, known as ‘The Big Five:’

- Explicit instruction in Phonemic Awareness.

- Systematic Phonics Instruction.

- Techniques to improve Fluency. These include guided oral reading practices where the student reads aloud and the teacher makes corrections when the student mispronounces a word. A teacher can also model fluent reading to the student. Fluency includes accuracy, speed, understanding and prosody. Word calling is not the same as fluency.

- Teaching vocabulary words or Vocabulary Development.

- Reading Comprehension.”2

Let’s take a look at each of these components in further detail, why they’re so essential, and how All About Reading and All About Spelling incorporate these components.

Explicit Instruction in Phonemic Awareness

Phonemes are the very smallest parts of a word – the sounds each letter or letter team makes. The word cat, for example, has three phonemes: /k/ /a/ /t/. Phonemic awareness is the ability to hear the word cat, break it up into its individual sounds, and identify the first, middle, and last sounds. A child with well-developed phonemic awareness skills can also manipulate the phonemes in the word cat, for example, changing the first sound to /b/ to make bat or deleting the first sound altogether to make the word at.

Often, children with dyslexia struggle to identify all of the phonemes in a word, which leads to missing, added, or changed sounds in words. It’s one reason why students with dyslexia often mispronounce words they hear or struggle to recall words accurately.

Effective reading and spelling programs, such as All About Reading and All About Spelling, will explicitly teach phonemic awareness so that students with dyslexia learn to notice the individual sounds in words. Through repeated exposure to activities such as phoneme manipulation (adding, changing, and deleting phonemes), segmenting words into their sounds, and blending sounds together, students become more attuned to each individual speech sound, which strengthens their ability to both decode (read) and encode (spell) words.

Our programs include activities, such as the Blending Procedure, “Change the Word,” and segmenting with tokens, which address and strengthen students’ phonemic awareness skills.

Systematic Phonics Instruction

In addition to struggling to identify each sound in a word, children with dyslexia often have trouble connecting the sounds they hear with the letters and letter teams (also called graphemes) that make those sounds. This is why young dyslexic learners might have difficulty learning the alphabet and letter sounds, and as they get older, may struggle to recall letter sounds quickly enough to read fluently or spell accurately.

Because we know that for dyslexic learners reading and spelling are like taking the circuitous mountain road, it’s as if those letter sounds sometimes get lost or mixed up on the back roads as they travel from long-term memory to language processing.

This is why it is crucial that students with dyslexia receive explicit, systematic, and incremental phonics instructions with plenty of built-in review. They need repeated practice identifying and connecting the letter-sound correspondences. This will help “rewire” the brain so that instead of taking the long way around, those letter sounds travel a faster, more direct route so students can recall letter sounds automatically and accurately.

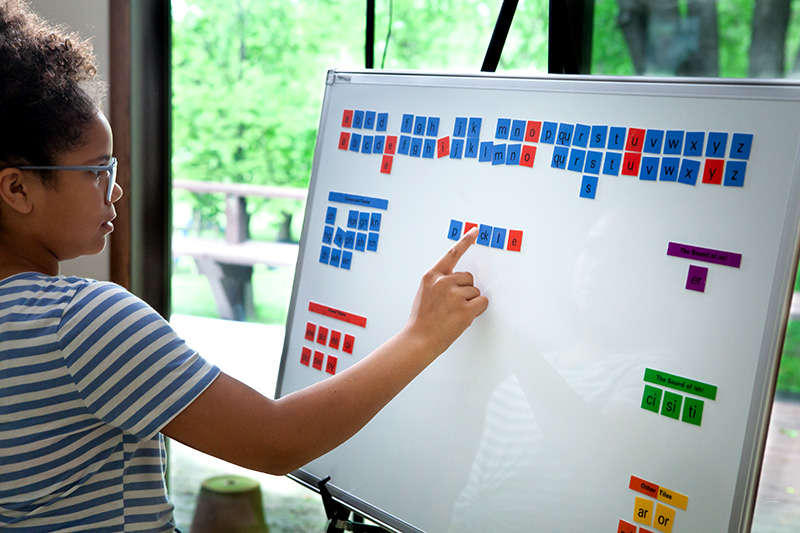

This step can take a lot of practice for dyslexic learners, though, and without this solid foundation, students may get stuck. That’s why All About Reading and All About Spelling include fully-customizable review boxes with phonogram and word cards for each program. Students review the phonograms daily until they are mastered, and once they are mastered, will continue to draw on that mastery as they read and spell.

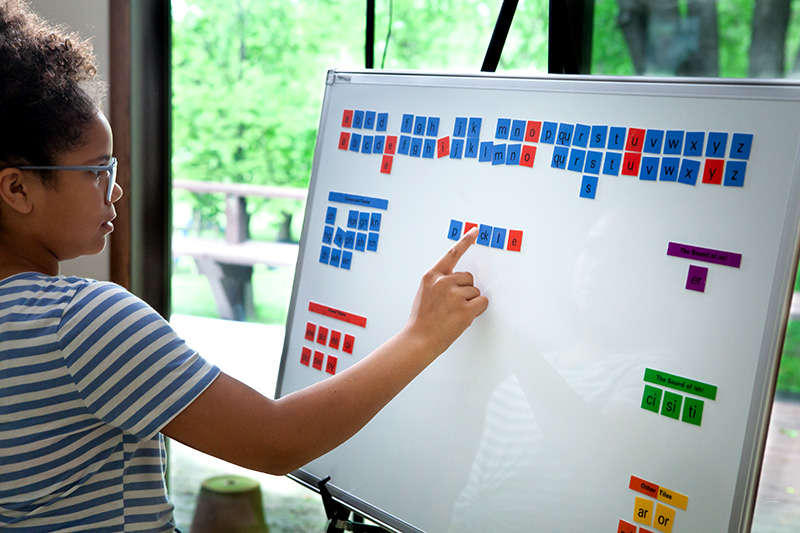

Additionally, our programs include the manipulative Letter Tiles, giving students multi-sensory experience working with the phonograms. This, in turn, reinforces their phonemic awareness as they continue to work with the individual sounds in each word.

Techniques to Improve Fluency

Reading fluency is an incredibly important skill. Sally Shaywitz says, “Fluency, the ability to read a text accurately, quickly, and with good intonation (prosody), is the hallmark of a skilled reader.”3 The reason fluency is so important, though, is because it serves as the bridge between decoding and comprehension.4 Without being able to read fluently, developing readers are stuck at the stage of laboriously decoding each and every word.

We tend to think that as long as a child can read accurately through decoding and word attack skills, they’ll eventually develop into fluent readers. However, that’s not the case, especially for students with dyslexia. Shaywitz tells us that “while accuracy is a necessary precursor to fluency, accuracy does not necessarily evolve into fluency. This is especially true of a dyslexic child, who is not able to call upon the specialized word form area and must instead rely on slower, ancillary neural pathways for reading.”5

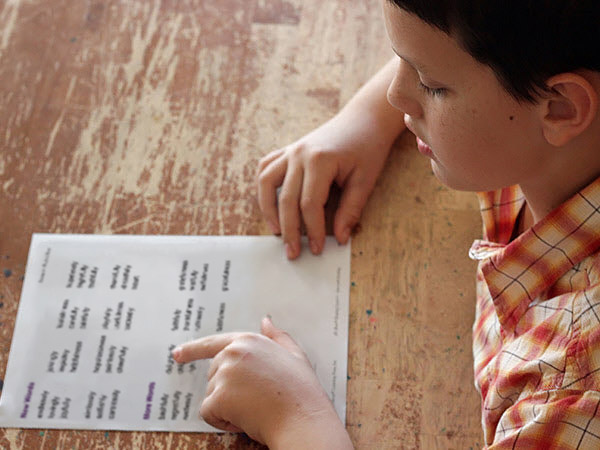

However, reading fluency is a learned skill just like any other. Successful reading programs will “focus on a child’s oral reading,” provide “opportunities for practice, allowing a child to read and to reread words aloud in connected text,” and provide “ongoing feedback as a child reads.”6

All About Reading meets each and every one of these areas through the use of the word cards, fluency sheets, and fully decodable readers. Our program gives students ample opportunities to practice reading connected texts aloud, receive immediate feedback from parents and teachers, and build their confidence as their fluency increases.

Vocabulary Development

Another important component of a successful reading program is vocabulary development. Having a large and diverse vocabulary is essential because as Shaywitz says, “A child does not simply open a book, decode the words, and magically understand the content.”7

In order for a child to understand what he has read, he needs the background knowledge and context that a large vocabulary can provide. In fact, “the size of a child’s vocabulary is one of the best predictors of his reading comprehension; children with the largest vocabularies tend to be the strongest readers.”8

The reason this is so important for dyslexic students in particular is because vocabulary words don’t just convey meaning, but they communicate ideas. The word they’re trying to decode is more likely to “spring to life if a child can integrate it with familiar ideas or with his own past experiences.”9 Fluent reading doesn’t occur in a vacuum. All students, but especially dyslexic students, need to be able to personally connect with the words in the text to give them meaning because they’re more likely to accurately decode and/or recall a word that has meaning to them.

Thankfully there are a number of ways both reading programs and reading parents can build a child’s vocabulary!

It starts when children are young by reading aloud to them – reading widely and reading often. High-quality children’s picture books are perfect for this, because many of them contain rich vocabularies set within delightful stories. As children grow and begin formal instruction, solid reading programs, such as All About Reading, will also increase a child’s vocabulary by pre-teaching words they may not know, teaching prefixes and suffixes, and teaching loan words from other languages. This gives students additional tools to make sense of words that may be unfamiliar to them.

Reading Comprehension

Finally, the whole goal of reading is comprehension. We read to understand, whether that’s the news, a magazine, a good historical fiction, or an academic text, the goal of reading is to take in and comprehend ideas.

The great news is that even though dyslexic students struggle with phonemic awareness and decoding, they are often really great at comprehension. Shaywitz says that dyslexic children’s weaknesses are “surrounded by a sea of strengths in higher cognitive processes such as reasoning, concept formation, critical thinking, and comprehension,” and that comprehension is actually “an area dyslexics can and often do excel in.”10

This can really boost a dyslexic student’s confidence, especially when a program addresses reading comprehension the way All About Reading does. By including sample discussions to have with your child before and after reading the stories in the readers, as well as questions to ask at various points during the stories, our program is designed to increase reading comprehension. Since this is an area in which dyslexic children tend to shine, these activities can really encourage dyslexic learners to persevere.

The Tools to Succeed

The research is clear that, with the right approach, children with dyslexia can learn to read and spell. If we provide the proper tools and interventions to strengthen those neural connections, we can “rewire” the dyslexic brain, teach our children how to overcome dyslexia, and take the struggle out of reading and spelling.

And as a parent of a child with dyslexia, that is something to get excited about!

To learn more about dyslexia, including the signs and symptoms in our Screening Checklist, head to our Dyslexia Resources page. And don’t forget to sign up for our newsletter to continue reading our “Dedicated to Dyslexia” series posts.

Learn more:

_________________________

1Orton-Gillingham.com. About Orton and Gillingham. https://www.orton-gillingham.com/about-orton-and-gillingham/

2Wooldridge, Lorna. The National Reading Panel and The Big Five. Orton Gillingham Online Academy. https://ortongillinghamonlinetutor.com/the-national-reading-panel-and-the-big-five/

3Shaywitz, Sally. Overcoming Dyslexia. 2nd ed., Vintage, 2020, p. 251.

4P. 252

5P. 253

6P. 253

7P. 258

8P. 259

9P. 261

10P. 300

Kayly

says:As a volunteer EFL tutor, I have so much to learn before I can help 2 teenagers, who I am sure have dyslexia.

This article has been extremely helpful.

Thank you so much for all the support I get from your blog.

Robin

says: Customer ServiceKayly,

I’m glad that this article was so helpful! You’re welcome.